MIMESIS OF AN ACTION

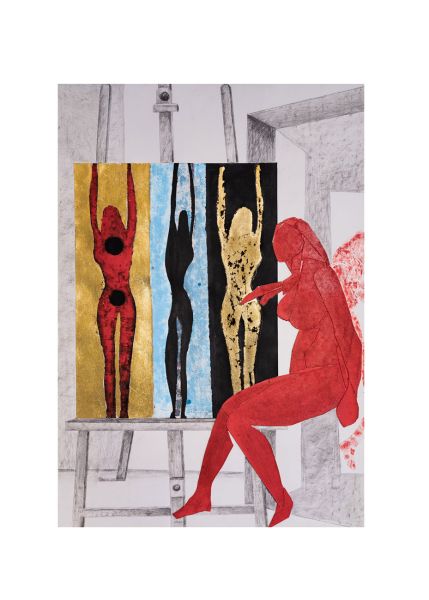

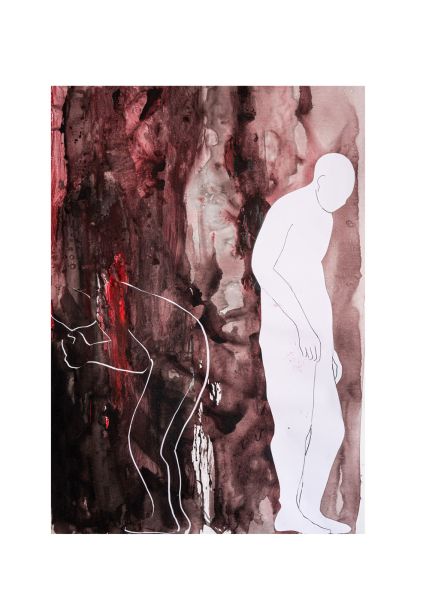

The title of my previous work, ‘ Οn body and soul’,(Depot Art Gallery, 2018) was an attempt to make the body ‘speak’. It comprised mainly collages decoupes of women’s bodies on sheets of cork painted red, and printed on paper. The imprinted bodies on the white surface of the paper were anonymous, devoid of a background story.

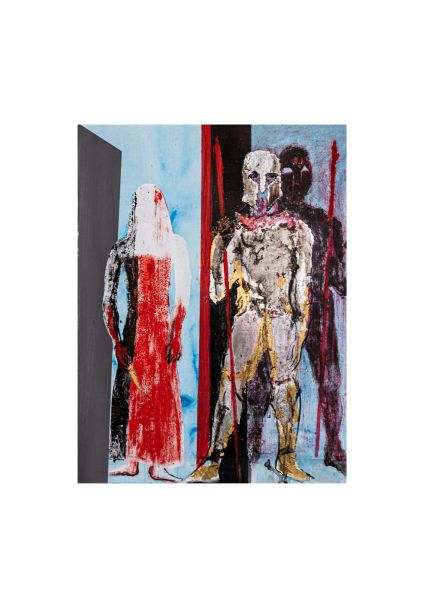

Αntigone, Iphigenia, Electra, Clytemnestra, Medea, Penelope, Phaedra, Agamemnon, Orestes, Creon, Oedipus, the figures of my latest work on the other hand are archetypal figures bearing both a profound story and global recognition.

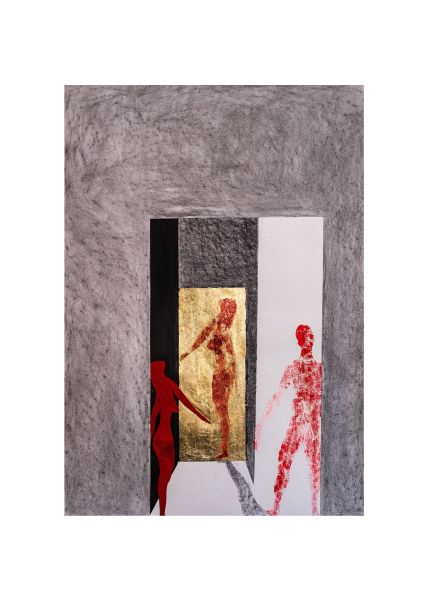

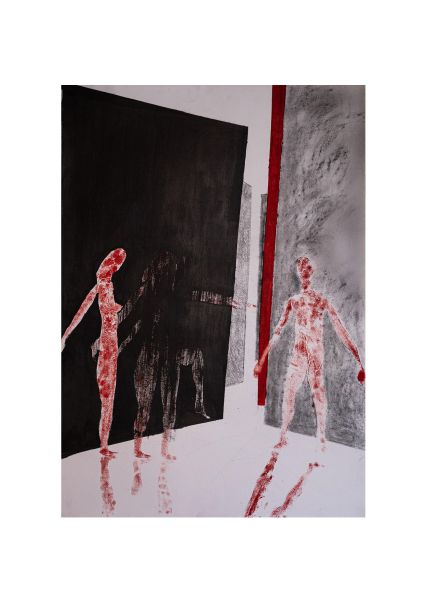

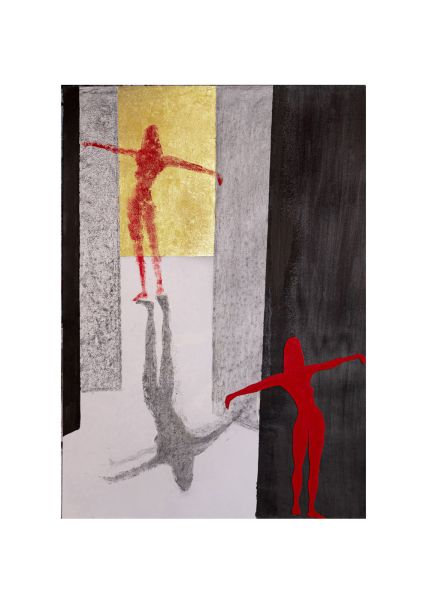

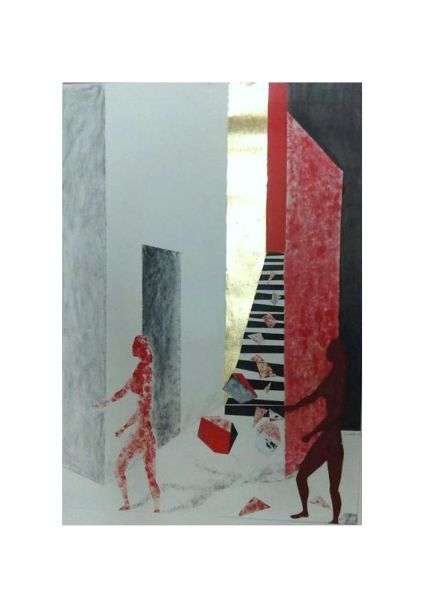

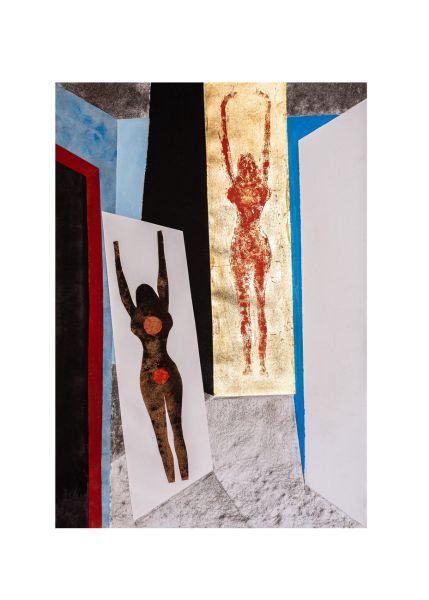

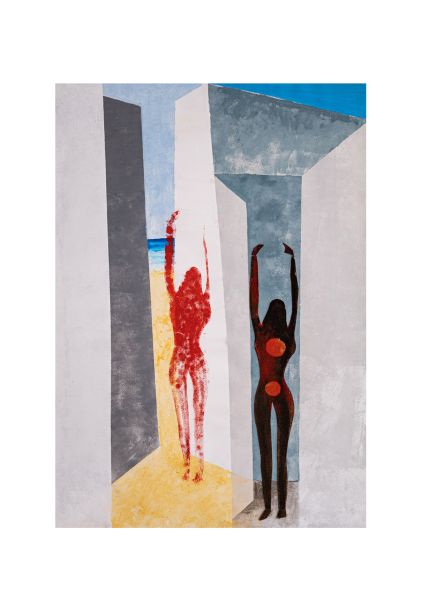

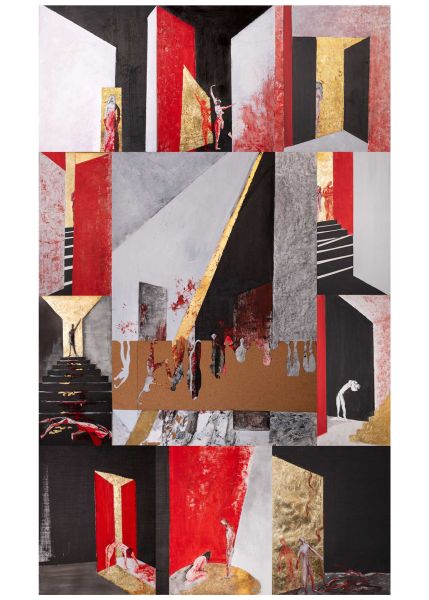

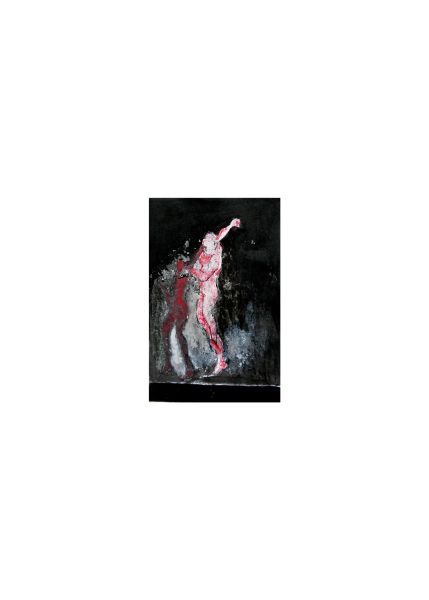

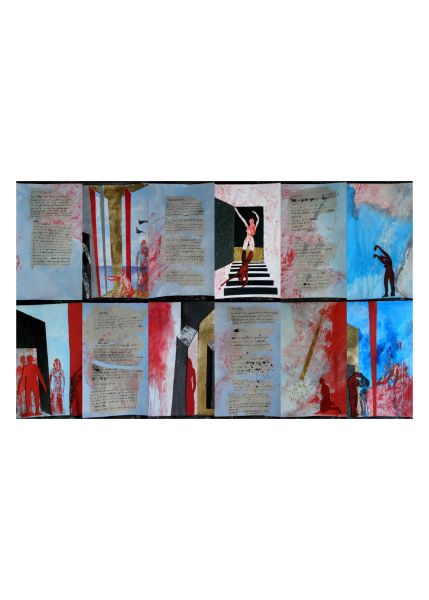

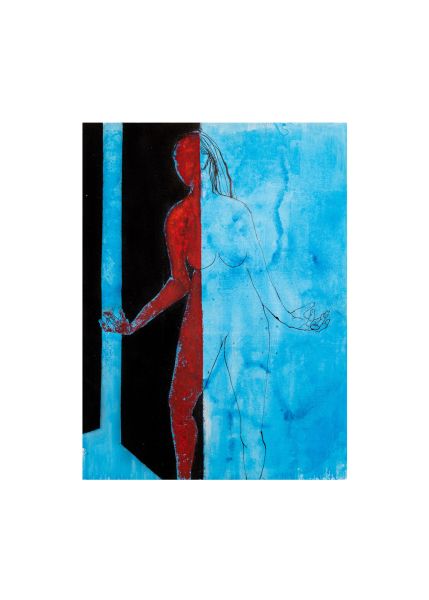

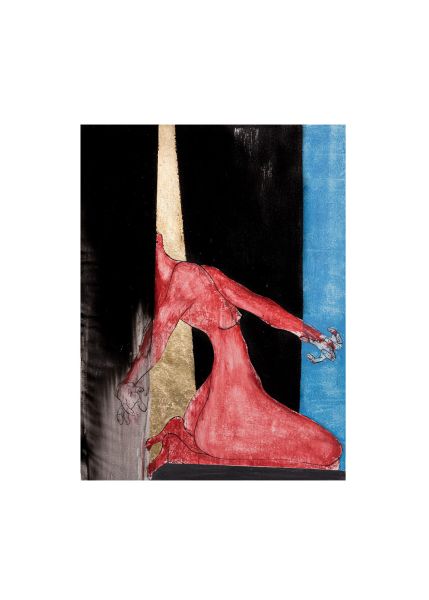

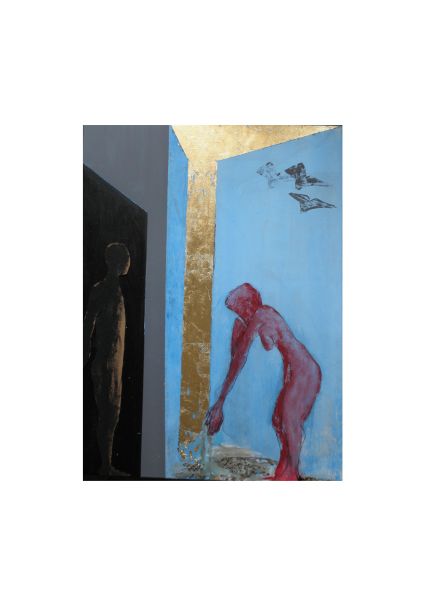

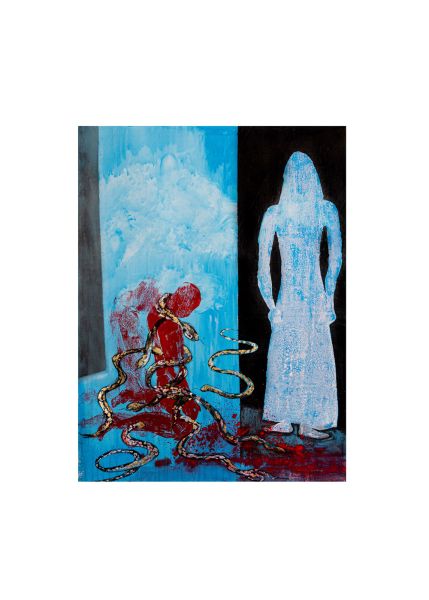

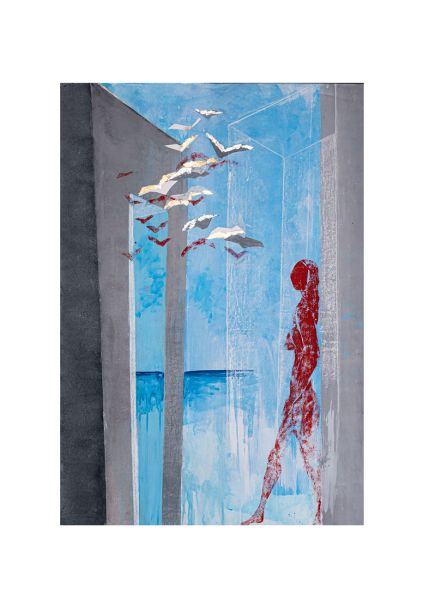

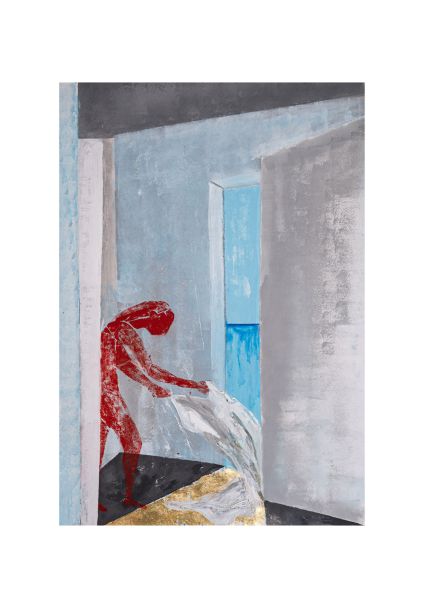

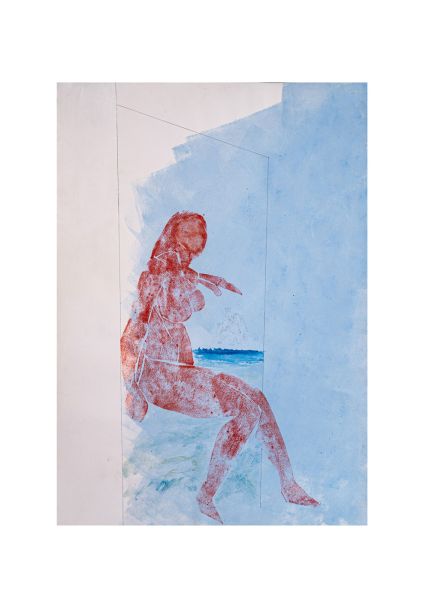

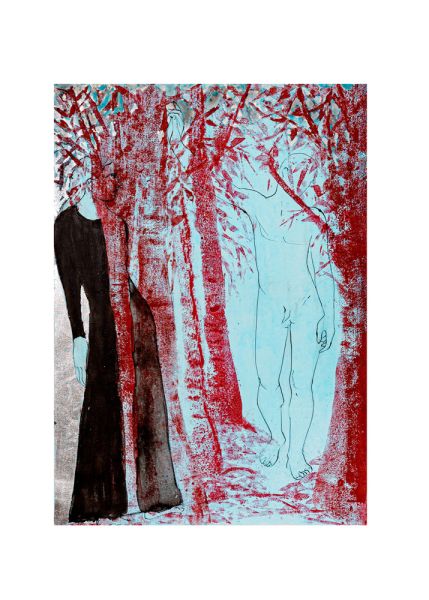

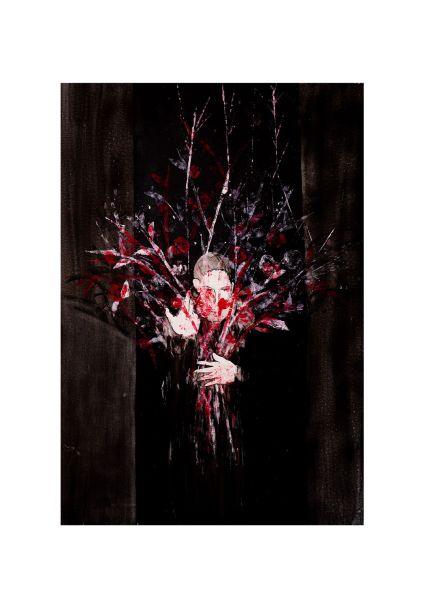

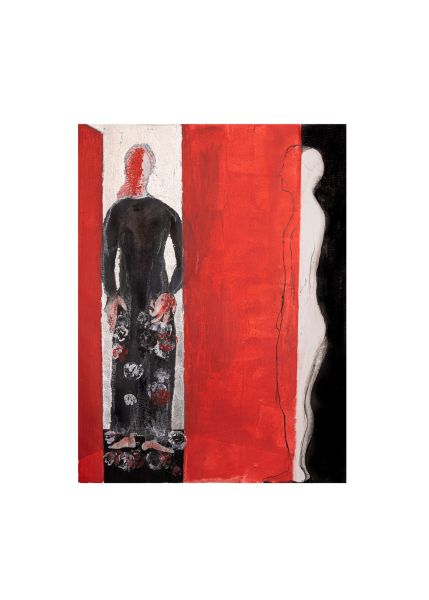

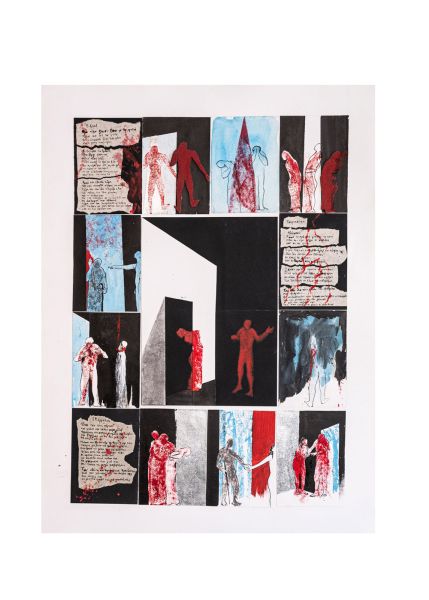

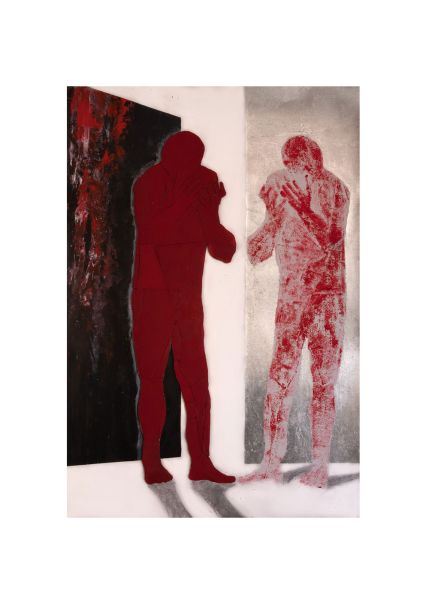

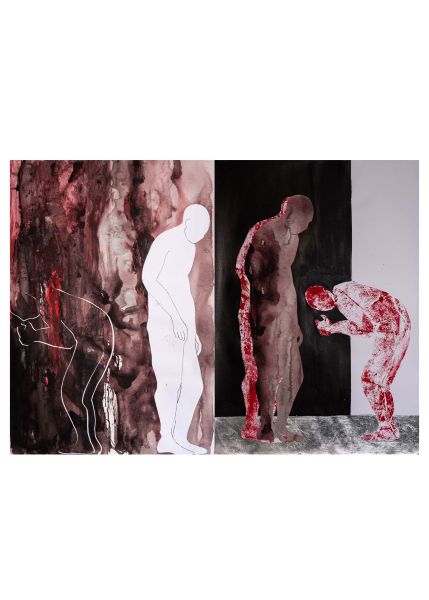

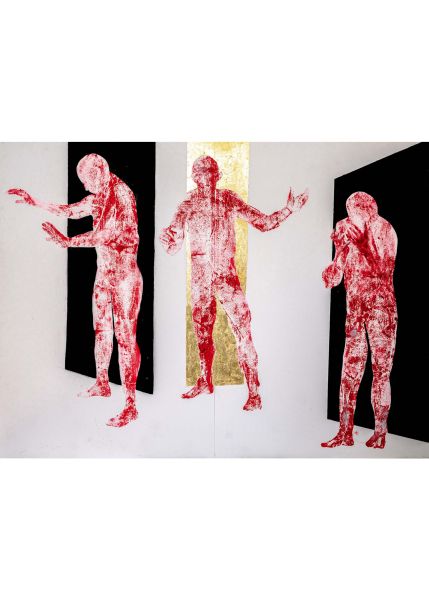

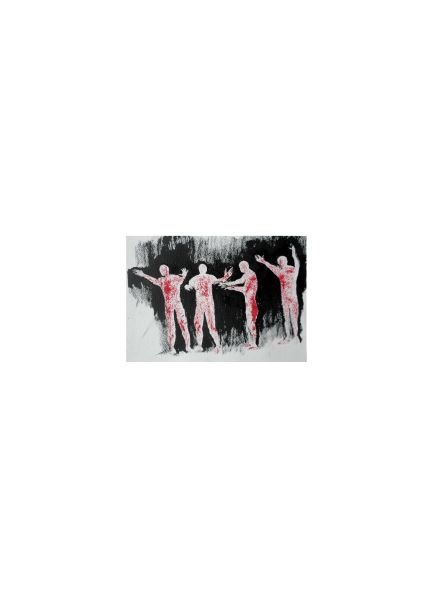

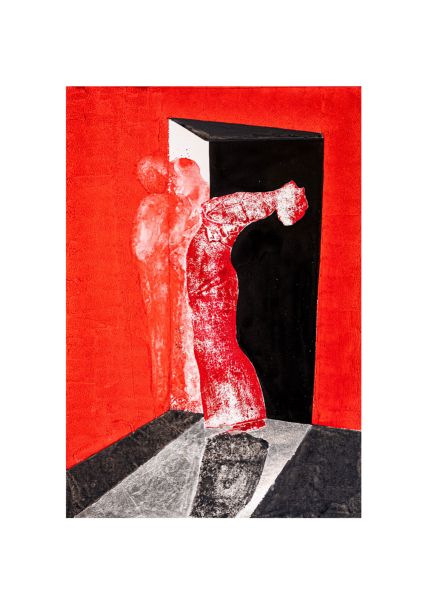

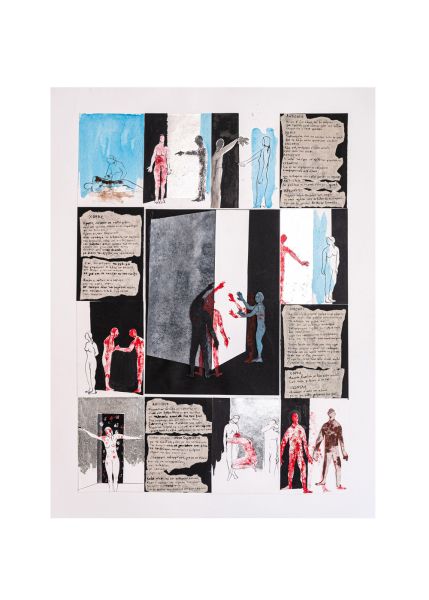

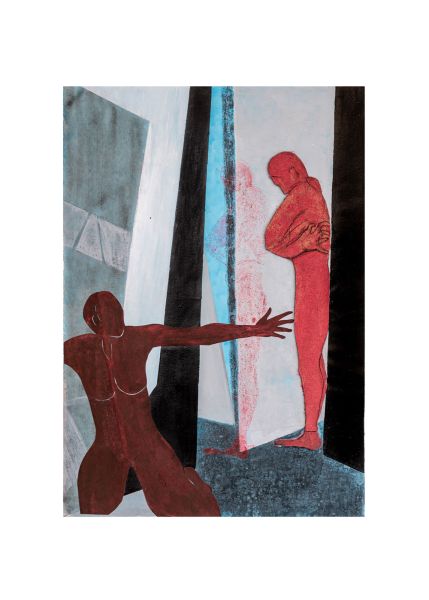

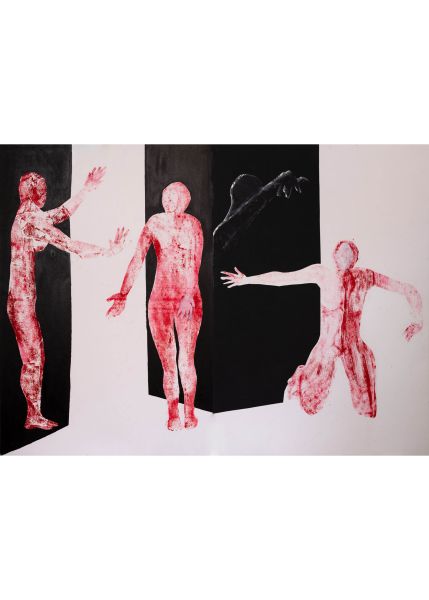

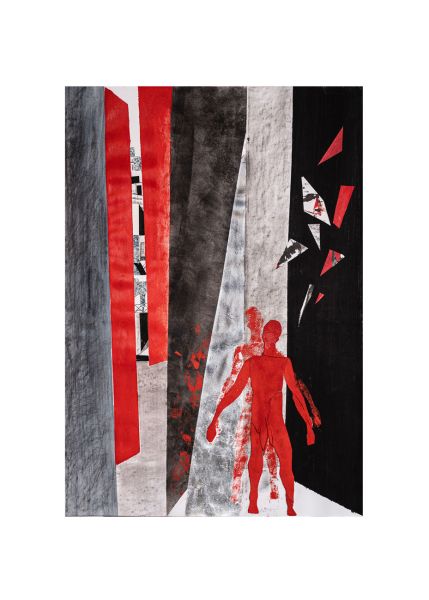

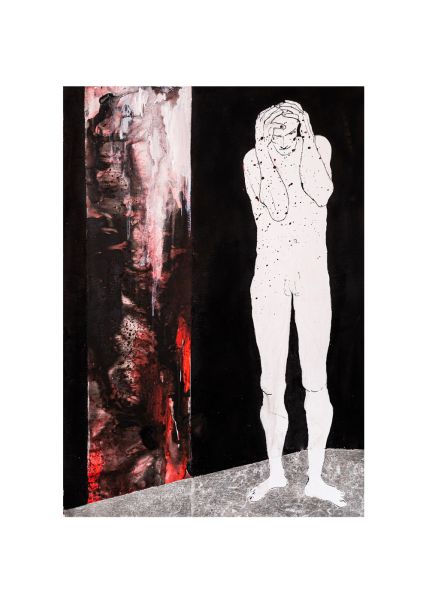

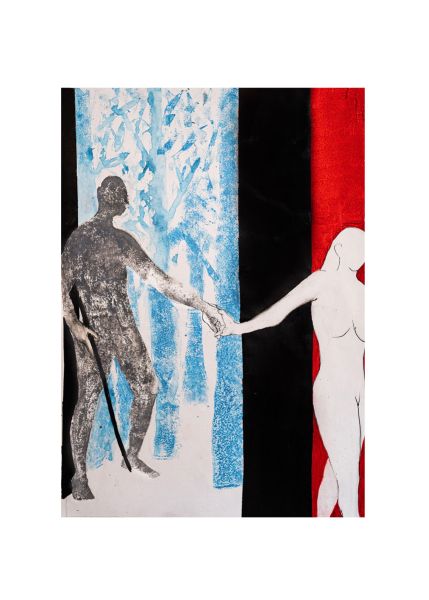

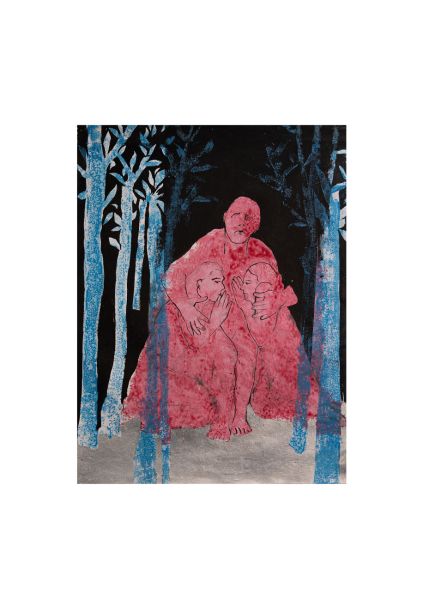

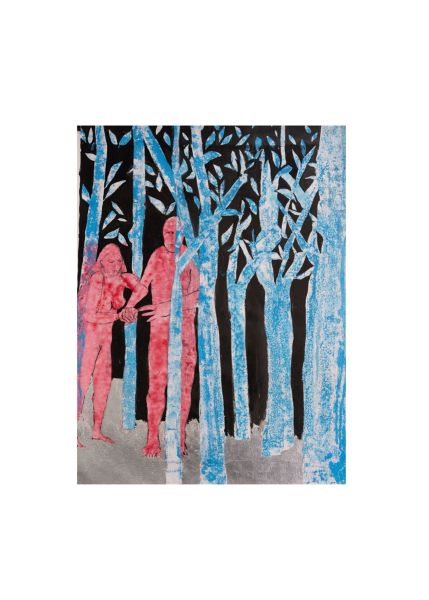

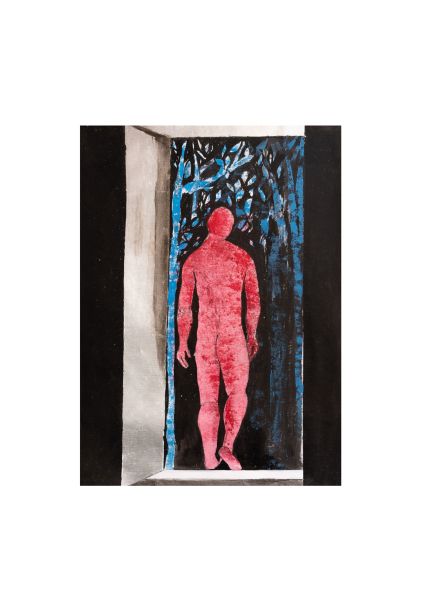

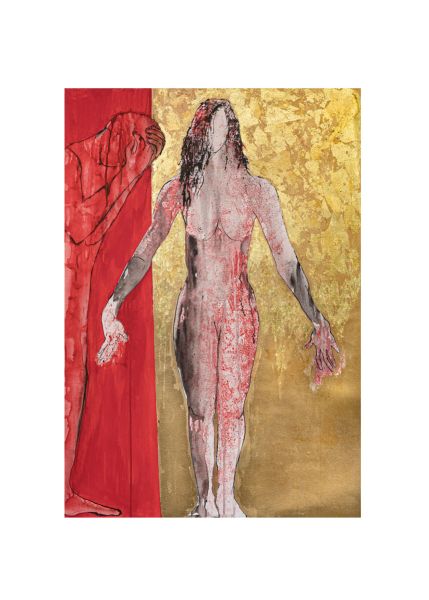

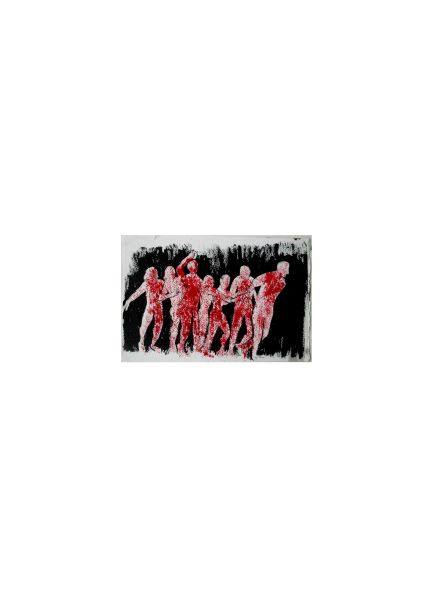

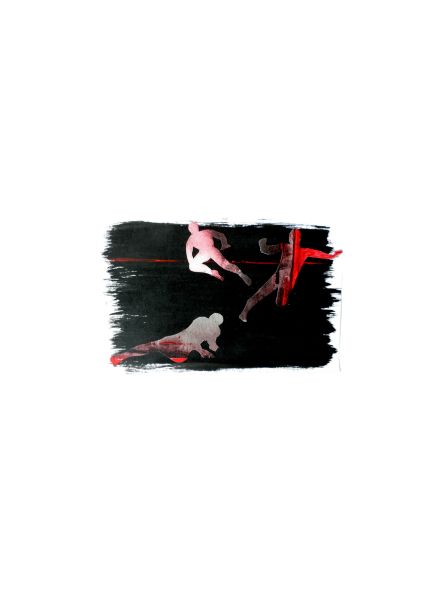

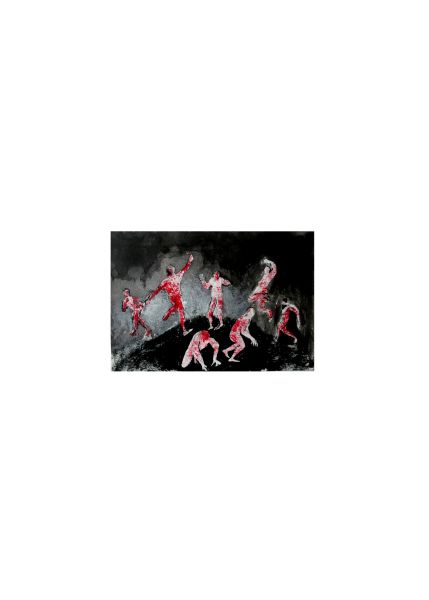

My approach continues to be focused on ‘the language of the body’. The technique of collages decoupes using cork and stamps has pursued me, at least in the initial stage of this work. However, what became imperative this time was the geometric availability of a location in which to receive the figures; a minimalist place, at times of symbolic significance and at others, a kind of scenographic frame in which the action takes place. Red, black, shades of grey, shards of gold on a white background. As the work unfolded, a watery pale blue was added and the bodies were drawn using pen and ink: Self-determined works, or multifaceted as the case may be.

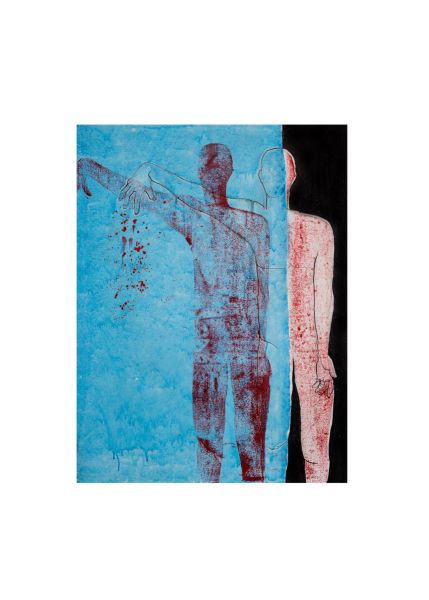

Internal conflict, the intensity of the tragic figures, their decisions, their actions, their confrontations, their redemption; the ‘human’ in its entirety which is at stake, expressed through the medium of art without the need for narrative or other graphic elements. The final pieces are the hands, the starting point of the whole work. I wanted to express the whole of the mental burden in a ceremonial manner. Antigone for example, opposes, resists, objects, talks back, proceeds unbending to her fate. Straightforward Creon imposes himself and at the same time is trapped. Penelope accepts, waits and welcomes. Clytemnestra revolts; arrogant in every personal confrontation. Cassandra, conversely to Clytemnestra, is delirious by her insightful feminine nature. Iphigenia, naive and innocent, falls victim to patriarchal compulsion. Stooped Electra mourns, mourns, mourns . Orestes is driven to matricide (I was particularly intrigued by this scene as one of extreme and repellent violence), weighed down by his feelings of guilt, then liberated, with blood on his hands, yet innocent. Agamemnon is a suit of armour, inaccessible, in the role of recruiter. Medea, wounded lover and mother (I took her figure from an Egyptian sarcophagus!) is guided ultimately to the light. Oedipus is struck by fate, stands and fights alone in a ‘universal’ flood. Phaedra quivers with covert erotic desire, vascillating between light and darkness, frustrated by the object of her desire.

Are we also not those figures? My need to refer to archetypes perhaps has to do with my sense that we are in danger today, in an era of virtual reality and ‘intact’ transactions, of losing the depths of human existence to a resultant outburst of irrational violence. And that is my artistic need. The catharsis of tired commercial prototypes. To grasp once again ‘the human’ with contemporary language.

Μato Ioannidou

February 2022

The composition of Mato Ioannidou

The questions that Mato Ioannidou explores cannot be answered via traditional philosophical enquiry, but through art. Observing the great tragedies, she views the world as a stage upon which human drama is ‘played out ’.This is how she has conceptualised her works: figures in the theatre of reality.

Tragedy is the poetry of the conflict between human will and the divine. Profound questions about freedom, fate, the concept of law, and the limits of morality are born of it; questions which are not amenable to pedagogical answers. These constitute extreme limits of the soul, and lead to rebellion. There is no tragedy without rebellion. The course of ‘man in rebellion’ is developed by the three great poets of Athens: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Eurypides. Their heroes – Antigone, Electra, Oedipus, Orestes, etc. – have still not resolved their suffering, even today.

Like the mythical Furies, these voices pursue the painter breathlessly. During the pandemic years, she gave these voices form, space; even wrote their utterances across her canvases. Transcribing verses from classical poetry, she discovered a goldmine of truths; truths that significantly determine how we might interpret ‘man’ and mankind.

‘I read poetry’ means, “I’m ready to get out of my comfort zone, insofar as I haven’t defined what it is and if I am comfortable”. This is how I first encountered Ioannidou’s works: figures that project like lightning in the dark, like a single sentence in the midst of a storm.

Without doubt, one can trace Ioannidou’s interest in the representation of movement to her theatre studies; a theme she has continued to explore in her depictions of actors and dancers. With purely modernist reductions, which echo the teachings of Matisse or the gritty emotion of our great engraver Vasso Katrakis, she renders the bodies without artifice, utilising the power of colour; often through outline alone. But she remains tied to tradition both in concept and in technique: she maintains the internal rhythm of the classical world without the urge to judge God or the world (I would even say that her gaze is shaped by her workplace: her workshop in the lap of the Acropolis).

In the constellation of the seven surviving tragedies of Sophocles, Antigone constitutes the brightest star, and it is to Antigone that the artist dedicates most of her works. When encountering Sophocles’ tragedy, it is impossible to focus on the sorrowful aspects of the work; rather, admiration for the heroine is forged. Indeed, all of Ioannidou’s heroes appear courageous in their defeat and all struggle with the loneliness that their heroism demands. In Aiades, Sophocles has Chorus describe the hero’s attitude with a term not found elsewhere in ancient Greek literature: O ἰβότας – and he means “one whose heart grazes in solitude” (vv. 614-5 by Jacqueline de Romilly in Ancient Greek tragedy).This term, I believe, perfectly encapsulates the isolation and dramatic expression evident in the work of the artist.

Mato Ioannidou has endeavoured to condense a rich dramaturgical universe to a powerful language that does not scream; solidly structured and geometrically strict in its means; each piece with its own individual presence and entity. And as a whole, her work acts as an encapsulation of a self-examined, and therefore liberating, drama of the minimum. Art reveals here the presence of another act that dares to the maximum through a single image.

The language of the tragic poets is multi-faceted, with countless aspects that shine in the light of dedicated reading, conveying the pulsating life of colours, the pulsating truth of life. The final – and in my opinion, most mature – work of the painter is not just a creation stemming from lengthy poetry. In the eyes of the viewer, it also unfolds as an action, a ritual. The public that will come into contact with the painter’s poetry will meet a Great Translator of ancient forms and visions into visual language.

Georges Mylonas, Historian of Art

October 2023